Disease: Coccidioidomycosis

Alias: Valley fever, San Joaquin fever

Learning about fungi is hard enough even for infectious disease fellows (Narrator: especially for infectious disease fellows). By the time you learn how to differentiate the yeasts from the molds, the fungi kingdom decides to throw you a curve ball: Enter the shape shifters into the game of fungi learning – the dimorphic fungi.

The Dimorphic fungi shape shift depending on the weather (literally). They exist as molds in the great outdoors (environmental temperatures) and yeasts in the great indoors (inside our bodies at body temperatures). Clinically, this also means you will see the yeast forms in a histopathology review of a tissue sample, and our friends in the microbiology lab can re-create the environmental factors to grow them out as mold forms in culture. So essentially, they also shape shift between the microbiology lab and the pathology department. (They are sneaky Fung(uy)i…).

If you haven’t read the posts on Histoplasma capsulatum or Blastomyces species, go read it now!

This is the 3rd post out of 6 and will focus on our third shapeshifter, Coccidioides species.

CLICK HERE for a 2-page PDF handout of this information.

Morphology(1):

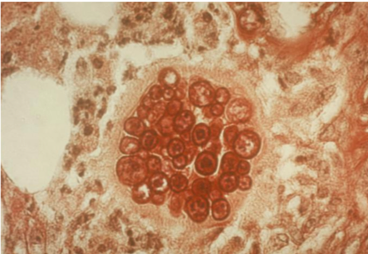

- This shape shifter differs from others in that it does not shape shift by temperature but resembles other shape shifters in that it exists as a mold in the environment and a spherule (Image) inside the body.

- Spherules are round, and contain endospores which are uninucleate and have walls and cytoplasmic inclusions

- Can be mistaken for yeast if only endospores are seen (but endospores don’t bud like yeasts!)

Geography, Reservoir and Mode of Transmission

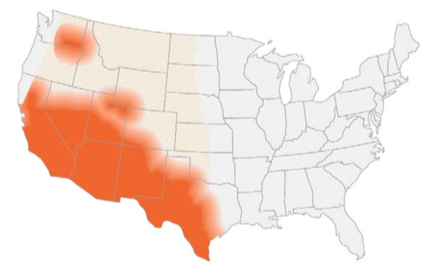

- Endemic in southwest of the US and certain arid regions in South America

- In the US, highest incidence in Arizona and California

- Reservoir includes: soil (increased during dry periods after rain/storms/earthquakes or excavation work)

- Mode of transmission: aerogenic

- Race predilection: Filipino and African Americans at higher risk for disseminated disease (Board favorite!)

Clinical presentation

- Two-thirds of individuals remain asymptomatic or develop self-limiting respiratory symptoms. When symptomatic → pulmonary involvement in >95% of cases(2)

- The disease can spread hematogenously to the following extrapulmonary sites: skin, soft tissue, skeleton, CNS (both meninges and spinal cord), eyes, heart, liver, kidneys, and prostate(1)

- Primary presentation often associated with skin findings (erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme) and rheumatological findings (myalgia, arthralgia)(2)

- Eosinophilia is often present!

- Unlike pulmonary nodules in histoplasmosis that often calcify, nodules in coccidiomycosis become small ‘grapeskin’ cavities, and cavities are often thin walled and can be associated with pleural effusions(3)

Diagnosis

Your friendly Infectious disease doctors will always ask for tissue, and if classic spherules are seen in histopathology or culture confirms growth, that’s a slam dunk diagnosis! But we understand that is not always feasible, so in addition to clinical history + presentation, in order of importance:

- Tissue/culture

- Serology (keeping in mind that it can be false negative very early on in the disease)

Culture:

*Please alert the microbiology lab if you suspect coccidiomycosis and are sending them cultures! (culture needs to be specially handled in the lab due to the risk occupational transmission/infection — just like all dimorphic fungi covered in this review series).

- Confirms diagnosis, growth usually detected 4-5 days (4)

Histopathology:

- Presence of endospore-containing spherules is diagnostic (see Image, Morphology)

- Tissue eosinophilia may be present, and as endospores mature into spherules,

- Granulomatous reaction predominates

Antigen detection:

- Urinary antigen not widely used, however urinary histoplasma antigen test could be positive in 50% of cases(4)

Serology:

- IgM usually becomes detectable within 1-3 weeks therefore negative serology early in the disease doesn’t rule out the disease

- IgG becomes detectable anywhere between 3rd/4th week to several months after becoming infected. This usually reflects degree of infection and can be used to monitor the disease(4)

- Increasing titers (or titers >1:32) may suggest dissemination(4)

Molecular methods:

- No commercially available tests

Management(5)

Pulmonary disease:

- Mild pulmonary disease: no treatment

- Asymptomatic nodule/cavity: no treatment

- Symptomatic chronic cavity: fluconazole/itraconazole (at least) for 12 months

Extra-pulmonary disease:

- Soft tissue/bone: fluconazole/itraconazole (at least) for 12 months

(*except for severe disease → Lipid Amphotericin B as an initial therapy for about 3 months)

References:

- Walsh TJ, Hayden RT, and Larone DH. Larone’s medically important fungi, 6th edition. ASM Press, 2018.

- Salzer HJF, Burchard G, Cornely OA, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Systemic Endemic Mycoses Causing Pulmonary Disease. Respiration. 2018; 96(3):283-301.

- Knox KS. Letter to the Editor: Perspective on Coccidioidomycosis and Histoplasmosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Medicine. 2014; 189(6):752-753.

- Saubolle MA, McKellar PP, and Sussland D. Epidemiologic, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of coccidiomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007; 45(1):26-30.

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(6):e112–e146